The wind pierced even the heaviest of overcoats. It did so every day. That’s what we got for living by an estuary. The ferry went every half hour. I’d get the 8.15 to get me to the office by nine.

That day I was late. Rosa being her delightful early morning self. She couldn’t find a shoe, her purse, her knickers. Attention seeking.

I missed the boat.

I stamped my feet, hugged my arms around my chest and made a fine impression of a Russian dancer. The overcoat fell limply from my body. Three years ago, when my mother had bought it, I could hardly move my arms it was so tight.

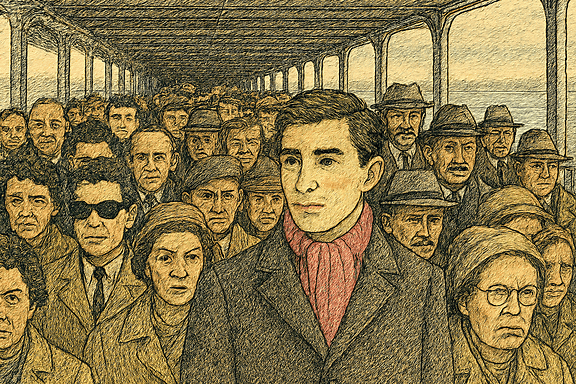

I glimpsed him looking at me: his muscular, slender frame; the pale green eyes spaced too widely apart, perched on the side of his face like a horse’s; the big wide mouth, and his little white teeth; his expensively-cut short hair (so he wasn’t in the Military); a coat, newer and better fitting than mine. He wore a pink scarf, neatly tucked under his clean-shaven chin.

Then there was the warm grin.

Our eyes met and, in that blink, the awfulness of my life revealed itself. Then a siren sounded. He disappeared into the crowd. I went to work and that evening returned to Rosa.

I stopped taking the 8.15, instead waiting for the 8.45. I never saw him again, but there has not been a week in the past fifty years that I haven’t thought about him.

Words: Richard Rooney

Illustration: A.I.

Flash Fiction 250